Although Colombia has one of the highest energy coverage rates in the region, 9.6 million people are considered “energy poor.” Eight percent of the population has no access to electric energy, 61.8% live in municipalities with erratic quality and 47.7% of the country still burns wood for cooking.

Energy poverty is acute along Colombia’s mining corridor. The recent and sudden exodus of numerous international mining companies as part of the country’s energy transition process has been devastating for communities long dependent on mining activity for jobs and income opportunities. How can these communities quickly benefit from the energy transition while building trust and interest in the broader, national-level process?

The departments of La Guajira, Cesar and Magdalena in Colombia.

The Governance Action Hub co-hosted its first co-creation workshop in Colombia with the University of Magdalena in the heart of the country’s mining corridor in early June to begin exploring this question.

Our earlier political economy assessment using SOAS-ACE’s “Power, Capabilities and Interests” approach suggested that supporting Colombia’s new enabling environment for a Just Energy Transition (JET) might be both feasible and impactful through the country’s new Comunidades Energéticas (CEs) initiative. CEs are coalitions of public and private actors that have legal status and can manage new forms of green energy, both for meeting community needs and for commercial resale to the national grid. The government is providing a range of incentives to promote CEs throughout the country, focusing on areas where energy poverty prevents people from leading full and meaningful lives.

Although our assessment highlighted that CEs would create feasible entry points for making systems change in the governance of Colombia’s energy sector, it underlined the risk for a considerable implementation gap between the government’s ambitious new policy and its impact at the local level. Without tailored support to communities to use the new investments as a disruptive force for inclusive local development, new policies and incentives were likely to remain bold commitments on paper only. In our hypothesis testing trip in March, we confirmed interest for CEs across a range of communities in different parts of the country but noted that not all had access to the information they needed about the government’s initiative.

Our analysis identified a need for coordinated action around a common vision so that private investors and different government entities could rally around local communities. Without this, it would be unlikely that new investments would be adequately owned or sustained, and the opportunity to use them as a disruptive force for better functioning local systems would be lost. Nurturing new practices and norms of collaborative governance for this new infrastructure could yield substantial benefits for local systems, extending far beyond the energy sector.

Our first co-creation workshop in Colombia

With the analysis in our pocket, we embraced the challenge alongside our allies at the Semillero de Transición at the Universidad de Magdalena.

We convened a range of actors: representatives from six different communities along Colombia’s mining corridor in the Cesar, Guajira and Magdalena departments, as well as the national government and local authorities, donors and organizations like Transforma, Global Green Growth Initiative, Polen and Insuco, among others.

Using a participatory approach to unpacking existing local systems, with an eye for the humans at their center, we invited the actors to a facilitated conversation:

- How might new investments in green energy help local communities achieve a collective vision of development?

- How would the present web of energy sector actors, all with different interests, capabilities and power, support or obstruct the implementation of such a vision?

- What would need to change to ensure that the investments would be useful to everyone, sustained over the long term, and lead to better collaborative governance practices in the energy sector and beyond?

Drawing a new future together, literally

Over two days of intense work with the communities and more than 50 participants and allies, we heard how energy access has the potential to transform the lives of children, youth, adults and elders. The groups discussed and produced visuals of new visions for their future, one in which energy access enables better education, better productivity and increased opportunities.

They drew detailed maps of local systems with specific insights into what must change for this potential to be realized.

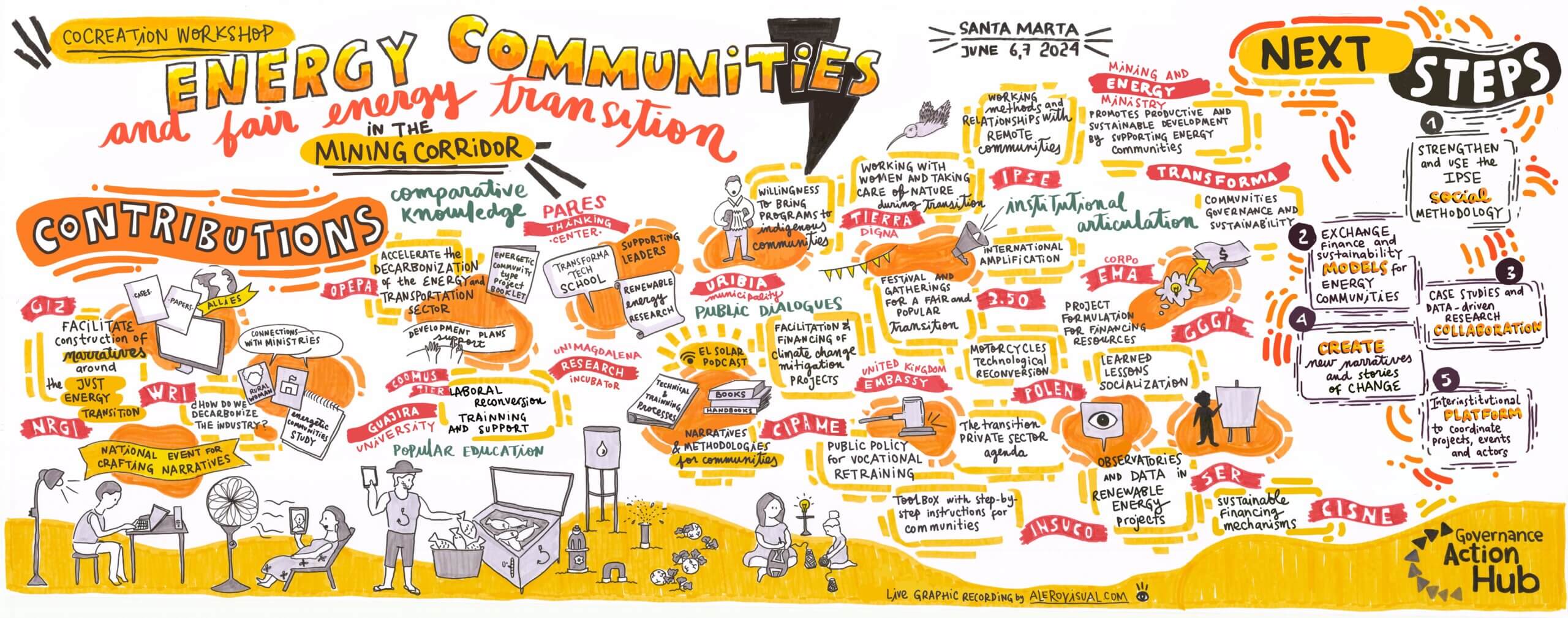

A graphic facilitator captured these maps so leaders could use them in their communities to engage additional perspectives and post a visual reminder of a collective goal.

Simply adding new technologies will not solve many local problems, the groups noted, unless there is more active presence and coordination among state actors, more empowered and inclusive leadership within communities, and clear business cases for the private sector to invest. The participants welcomed the workshop as a first attempt to help make this happen. In a final session, we mapped together how a new and improved system might emerge from the present, more challenging one.

Taking steps together toward change

Many allies present were eager to accompany this emergence and provide continued support.

Together, we defined five areas and formed working groups to act and maintain momentum:

- Social Support for the Training School for a Just Energy Transition

- Exchange of Technical Capacity and Sustainability Models

- Knowledge Projects, Research, and Case Studies

- Capture and Dissemination of New Narratives

- Inter-institutional Coordination

A forthcoming blog post will explore the groups’ upcoming steps in more detail.

The Governance Action Hub will continue to link disparate components of the solution. Our participatory systems design methodology was well received — in fact, one organization announced it would use the methodology to support its work across the communities it is accompanying in the mining corridor.

The workshop was a modest input to test a new methodology and explore whether actors working together can produce more than the sum of their parts. It was also a reminder that many problems cannot be solved solely with large amounts of financial resources. In-depth understanding of local systems, the actors and existing processes and norms is a good first step.

We hope that as we, alongside our allies, move forward in Colombia, we can help the country achieve its goal of 20,000 Energy Communities by 2026. It is an ambitious goal.

Local processes and behaviors often take time to change. Balancing ambition with a realistic pace of change will require attention. Specific interventions at the meso level (in this case, between communities) and the national level to ensure the broader system is supporting sustainable local change at scale are also needed. But if change at the local, meso and macro levels in Colombia can emerge, perhaps the country can continue to teach us all about the tangible benefits of systems change and the lives that benefit when it happens.